![]()

Shorts

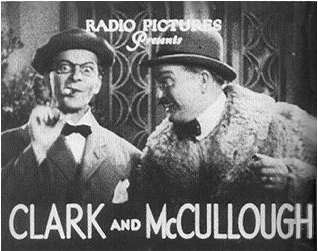

Contrary to what I had previously believed, I know now that at least some of Clark and McCullough's RKO shorts were released to TV during the 50s. Moreover, RKO itself re-released some C&McC titles into theaters around 1949-50. The long and short of Clark and McCullough's failure to make their mark in the 50s is that, not only was their comedy frequently too adult for kiddie fare, it was also too esoteric. Even in their own time, Clark and McCullough's shorts stood out as singularly strange, and contrasted with the comfortable similarity of the Three Stooges shorts or the sympathetic, carefully crafted Laurel and Hardy films, Clark and McCullough's RKO series is downright alienating. More so than any other comics of their day, the team had no use for sentimentality or even likability. The laugh was paramount, no matter how it was achieved. Everything's Ducky (1934) must stand as one of the cruelest, most perversely funny shorts of the 30s, with Clark and McCullough cooking and serving up a man's own pet duck to him at a dinner party. Bobby and Paul stand as the ultimate comedy anarchists of 30s film due to the unsurpassed disregard for form and general humanity that the team had brought with them from the patently unreal world of burlesque. But film creates its own reality and Clark and McCullough's humor can be argued to be too outsized and too aggressive for a medium as personal as film. Even the Three Stooges' violent slapstick was tempered through the use of cartoonish sound effects. Clark and McCullough, who had abandoned the pursuit of any kind of serious career in film following what they considered to be a "failed" run at Fox, treated their RKO series lightly, shooting during the off-season and probably viewing the films as little more than advertisements for their stage work. It was undoubtedly easy money for the team. The resulting devil-may-care quality gives their best shorts, such as Odor in the Court (1934) something of an edge, but, at worst, it can spiral down into sheer sloppiness, as witnessed in The Gay Nighties (1933) and Fits in a Fiddle (1933), both of which feature performances from Clark that feel like rehearsals. It's hard to believe that he wouldn't have demanded retakes if he had viewed the rushes, but I have my doubts that Bobby and Paul were that engaged with the process at RKO (which makes me wonder all the more about their much more prestigious Fox series, which had a sizeable budget and both Clark and McCullough's eager participation). Two-time Clark and McCullough director Sam White (brother of Jules) summed up the paradox of the team in an interview with David Bruskin:

"The thing about Clark and McCullough was that when you directed them on the set, they were hysterical, especially Bobby. I used to think that the scenes I was making would split my gut. When we got it on film, it wasn't funny. They just never came off funny. They exuded some kind of chemistry in person that never came off on the screen as it should have."

-Bruskin, David N. The White Brothers. New Jersey: Metuchen, 1990.

White goes on to argue that the only way he and directors Mark Sandrich and Ben Holmes could make the team funny on film was to load their comedies with slapstick, something that may be true for White's two films but not at all true for Sandrich and Holmes' efforts, most of which contain a lot of the "personality things" that White claimed didn't play well with preview audiences. In any case, the stage v. screen paradox of Clark and McCullough's style can, in my opinion, be attributed to context. What reads as funny in the here and now may not seem so clever once it's removed into the new context of film, a medium hyper-real and yet fundamentally illusory. Interestingly, the opposite was repeatedly claimed of silent comedian Harry Langdon, who appeared to be exuding not much of anything during filming, but whose delicate miming came to life thanks to the camera's attention to detail. As far as I'm concerned, Clark and McCullough come across very well more often than not, and even their worst shorts are worth a look. Ultimately, the team's output for RKO is a mixed bag that seems to be something of a Rorschach test for classic comedy fans.

Features

By the time Clark and McCullough had left Fox and their film ambitions behind, the Hollywood gold rush for Broadway stars was simmering down, and so was the "anything goes" vaudeville aesthetic, so in vogue during 1929 through 1931. The team had undoubtedly participated in this aesthetic while at Fox.. they had certainly helped to usher it in as two of the first Broadway-to-Hollywood transplants in 1928.. but the window of opportunity to make headway in features was closed. Their first major Broadway "book" show, The Ramblers, was shot as The Cuckoos by RKO in 1930 and starred the studio's resident comedy team of Wheeler and Woolsey. It seems unlikely that Clark and McCullough were even considered to reprise their roles as Professor Cunningham and Sparrow as a) they were then appearing in the biggest critical success of their careers, Strike Up the Band, on Broadway and b) RKO most probably purchased the rights to the already four-year-old Bolton-Kalmar-Ruby play exclusively as a quick, ready-made vehicle for Bert and Bob (who would go on to shoot another three movies that year). All of which begs the question of why The Ramblers wasn't shot as a feature by Fox while Clark and McCullough were under contract there. Tailor-made as it was for them, The Ramblers would have given the team a good start in features at a time when the type of comedy they excelled at was very much in style and, pending its success (it would have been hard to fail with such a film in 1929), it would have allowed Clark and McCullough to develop and fine-tune their approach to screen comedy as the talkies evolved. Sadly, Fox did not seize the opportunity, and by 1930 the team was out of the running for work in features, being neither personally interested or actively considered by the studios. The only film that came close to a Clark and McCullough feature was the five reel Fox featurette Clark and McCullough in Holland (1929), considered lost.

Meaningless Speculation

It's interesting to note that, by 1935, Clark and McCullough's RKO shorts were beginning to tend away from pure nonsense comedy and more towards farce. Certainly by 1935, the brand of humor that Clark and McCullough had specialized in for almost two decades was steadily falling out of favor, and it's hard not to see Alibi Bye-Bye (1935) as an attempt to find a new direction for the team in film. Uncertain as I am about the circumstances surrounding the team's departure from RKO, I can't say with any degree of certainty whether or not the team would have been likely to return to film had McCullough not died in 1936. I personally think it unlikely that Clark and McCullough would have remained in shorts past 1937 given the evaporation of the shorts market and the fact that the only viable alternative to RKO was Columbia. The notion of a Jules White or Hugh McCollum produced C&McC series is, besides doubtful, pretty bizarre. The pay would have been questionable, Clark would have been unlikely to take Jules White's micro-management kindly, and the team's style would have been highly unsuited to the kinds of formulas Columbia shoehorned most of its comics into.

As for the team itself, it's hard to say. McCullough's suicide undoubtedly clarified Clark's career path, and I find it hard to imagine that anyone truly thought it possible that Clark, given his ambitions, would have retired from the stage following his partner's death. He bounced back within six months, taking over from Bob Hope in the second production of the Ziegfeld Follies of 1936. Without McCullough, Clark, who had been appearing more and more frequently on stage without his partner anyway, rapidly moved into roles that would have precluded any kind of double act. It's very likely that McCullough realized that the days of the partnership, as it stood for almost three decades, were numbered no matter what Clark's reassurances may have been, although whether this played any part in his nervous breakdown and suicide is a matter for further speculation. Had he lived, I think it most likely that Clark wouldn't have dissolved the partnership, but rather made it a sometime thing, appearing solo more often than not and working with McCullough given the appropriate vehicle or venue. Where such an arrangement would have left Paul is unknowable, although I cannot believe that Bobby would have ever cut his friend loose, financially or otherwise. One way or another, Paul McCullough was facing definite declining personal prestige by 1936, a prospect that may have looked even worse from the perspective of the man who was not only once the team's comic (perhaps explaining why Clark and McCullough's "comic first" billing flew in the face of tradition. With Paul as the comic, it would have been well in keeping) but who had also urged his younger friend into show business in the first place.

-Aaron Neathery 10/13/06